John Drawbridge. New Zealand House Mural, 1963. Oil on canvas panels.

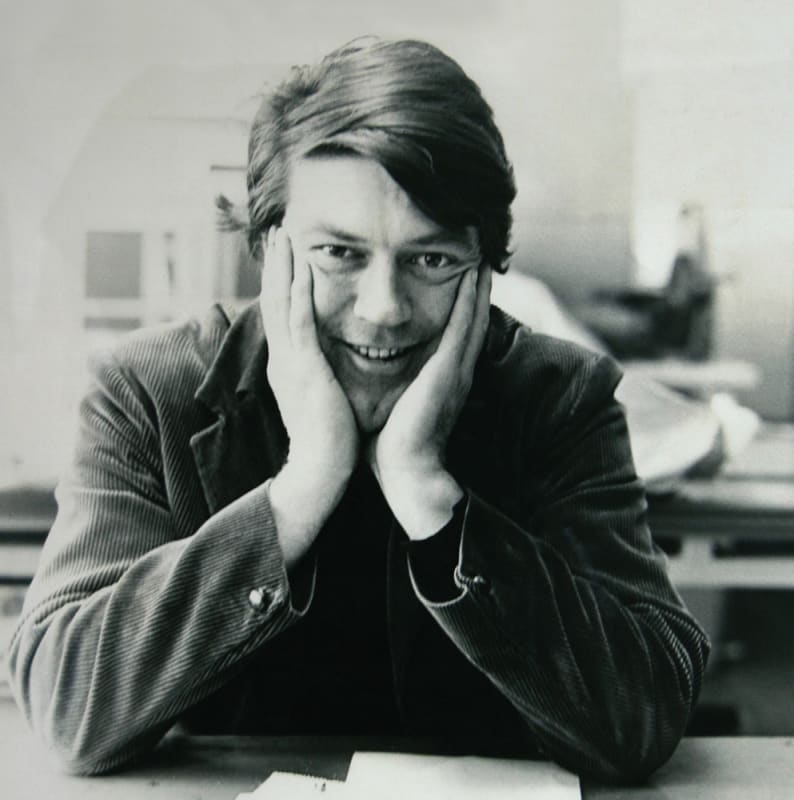

1963, London. A thirty-two year old New Zealander has just found himself at the beginning of a fast upward trajectory through the British art world. The Redfern Gallery, famous for showing the works of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth while they were still students-and, critically for New Zealand, one of Frances Hodgkins' main London dealers-mounted an exhibition of this Wellingtonian's works. The Rothschild family purchased a work, as did both the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert. He'd been shown in a summer exhibition alongside the likes of Picasso and Matisse; The Guardian had reviewed his works well. The same year, the artist won a commission to complete a monumental mural for the newly completed New Zealand House, a work that to this day remains one of the high points of twentieth century New Zealand painting, matched only, perhaps, by McCahon's Northland Panels. His name is spreading fast, he has other dealers courting him wanting to show his work, and he's the envy of the group of New Zealand artists living in London at the time (Ralph Hotere, Melvin Day and Don Peebles, among others). And then, seemingly just at the point of real breakthrough that every young artist dreams of, this young abstract painter and printmaker decides to move back home to the end of the Earth, settling with his wife Tanya, a well known silversmith and sculptor, in a house in Island Bay, Wellington.

Why? Why did he move back? It was a decision that others would wonder about for the rest of this artist's life. John Drawbridge himself, however, remained resolute. In his decisions and in his art, Drawbridge stands as a figure comfortable with the doors he has closed. It's a kind of wisdom-something that this artist had in no short supply, as those who knew him attest, and as his work so clearly demonstrates.

It certainly wasn't easy in Wellington, in those days, as Rita Angus and Gordon Walters likewise knew. When in 1967 one of his wonderful geometric, textured works called Coastline, Island Bay was chosen by the New Zealand Government to be a gift to the Canadian Parliament, Drawbridge had to suffer the ignominy of a local newspaper publishing the painting and asking readers whether it looked to them like the Island Bay coastline (the implication being, of course, that abstraction was a joke because it did not represent reality faithfully). Why he didn't get on the next ship back to London is a mystery to me. Drawbridge stayed, however, to New Zealanders' collective benefit. And to thank him, we-with a few critical exceptions-forgot about him in favour of those artists who were Kiwis through-and-through. Artists were encouraged to go for their "OE", as Gordon Walters did in 1950, and as Angus and McCahon did in 1958. But the imperative was always that whatever they did, they mustn't have too much success over there, or get too directly influenced by those tricksy modern tendencies. And if they did? Well, they'd be better off staying in London, like Frances Hodgkins did. Then we'd claim them as ours after they were dead, as if we'd been their greatest supporters all along. (The Canadians, by the way, loved Coastline, Island Bay so much that they asked for another of Drawbridge's works).

It's not that Drawbridge was neglected entirely, but he was placed, after his return to Wellington, in what one of his friends from the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London called the "artistic wilderness". He was there because of a few choices he had made. First, he lived in Wellington-a fact that made him practically invisible to this country's art market, which operates primarily in Auckland. Second, in addition to his painting, Drawbridge was a lifelong printmaker, specialising in the mezzotint method (a process that, when practised as well as Drawbridge did it, produces stunning contrasts of light and dark, and a richness in colour not possible with other methods). What in retrospect seems a complement to his painting practise was not seen so at the time: printmaking of all kinds is to the art market a distant cousin to painting itself, a method good for making a quick buck and popularising an artist's work, but not at all "serious". Drawbridge was always more than just a painter, and printmaking was an essential part of his practise-for it, he was outcast. And third, again in the words of Drawbridge's friend Robert Macdonald, who wrote his obituary in The Guardian in 2005: "His (Drawbridge's) paintings were poetic and concerned with colour and the often subtle effects of light. They were very unlike the darkly brooding effusions of his more famous contemporary, the Auckland-based painter Colin McCahon, and so did not fit neatly into curatorial ideas of what New Zealand painting should look like. They were a bit too international in spirit and perhaps a bit too joyful."

Joyous and international in spirit-these are the defining characteristics of Drawbridge's work, the features that were irrepressible during his devoted fifty-year career. To see his 1963 New Zealand House mural in the twenty-first century is almost to rediscover New Zealand. No more brooding, no more melancholy, no more Manuka in bloom breeding despair. No more muddy hues, faux-"primitivism" or local landscapes. Instead: light, and energy, and dynamism, and colour, and seasons, and all the loveliness of the spirit of this country that "all too often goes unnoticed", as the writer John Mulgan so long ago opined. At far left, a bright, burning orb of light sets the stage, while at far right, the deepest blues and greys of last light dominate-between these extremes, swirling, combed forms stretch across and move around the canvas. In places the colour and light are as soft and melancholy as Fra Angelico's are at the Convent of San Marco in Florence; in other places, like just to the right of the centre panel, the blocks of colours are so rich, intense and geometricised that one thinks of Kazimir Malevich's Suprematist Compositions of the mid 1910s. Seeing the painting in person for the first time at Wellington's City Gallery I was left laughing out loud-laughing, because why could I not see this country this way before, and laughing, because how could such a monumental painter be so unregarded? I felt, seeing this mural, that I could conquer the world from Island Bay; and I still feel that way even just conjuring its combed forms and regal colours in my mind.

In the mural, which hung for many years in the foyer to New Zealand House in London before being repatriated, Drawbridge captured New Zealand. It is not a landscape, or a seascape, or a skyscape, or a cityscape, but rather all of those, at once. It is not sunrise or midday or sunset, but expresses all of those times of day-at once. There is no recognisable place. It is not New Zealand seen from the top of a hill, but New Zealand seen from thirty-six-thousand-feet above, or half a world away. "My intention is to convey a sense of the patterns of the movement of light over water and land", Drawbridge wrote upon the painting's completion: "There is the continuous flow of a kind of cross-section of the New Zealand landscape." Never before, and never since, has a New Zealand artist tried to capture so incorporeal a sense of this country, and nor have they done so from the distance of London. (Not that we should be surprised. For does any country ever learn as much about itself as from its expatriates?) This is not provincial NZ art, a nice advertising project for New Zealand House. This is art of the very best kind, grand but never touching on grandiosity.

John Drawbridge. Window, 1972. Oil on canvas. Private collection, Wellington. Copyright John Drawbridge Estate.

And there, somewhere between the borders of New Zealand and the porousness of international artistic styles, is where Drawbridge's work most often resides. This country is never dealt with recognisably, naturalistically; instead we read it into the work through the artist's biography, the work's title and the constant play of ocean, earth and light. Window of 1972 is a large canvas, over two metres high, where we look out-as if through a window or door frame-on pure colour. It is a seascape, but one glimpsed perhaps through bush or forest at a time of day when the sun is just low enough to shine directly into your eyes so that all you see are masses of colour. It is indeed a joyous work-one international in spirit, but to a New Zealander feeling rooted in a time and place.

At other times, particularly in later years, Drawbridge seemed to delve deeper than ever into art history. He engages directly and unashamedly with the art of all periods, proving-and therefore opening the door to other artists in this country-that you did not need to be in Italy, the Netherlands or Russia (for example) to engage with the best art to have been created in those places. I think of his 1984 watercolour Vermeer, Rembrandt and Malevich, where these artists' works come together in an interior-like setting: viewed through a doorway we see Malevich's Suprematist compositions hanging on a wall, with abstracted figures from Vermeer seated before them-and to the right, in a different space (and actually on a piece of card then pasted to the watercolour), hangs one of Drawbridge's own prints from the year before of a detail from Rembrandt's Night Watch. This is a secularist's sacra conversazione, a kind of holy conversation between artists from different times and places. Vermeer's intense naturalism meets-and enjoys meeting-Malevich's pure, tensile abstractions from over three hundred years later.

John Drawbridge. Vermeer, Rembrandt, Malevich, 1984. Watercolour on card and paper. Private collection, Wellington. Copyright John Drawbridge Estate.

The work has a greater meaning to me: it is the first artwork I ever consciously knew. Hanging always on my parents' living room wall, I remember looking into this interior space and wondering about the artworks and the colours and the lives of the figures depicted. Long before I knew Vermeer, Rembrandt or Malevich-long before I was consciously interested in art-John Drawbridge taught me, a child in Wellington, New Zealand, about the limitless depths and the irrelevance of geography to the great artistic conversation.

John Drawbridge was not forgotten by the London art world, with his obituary written after his death in 2005 in most major British papers; but he never again was part of it. And so why, again, did he leave England, on the cusp of the success that most artists spend their lives hoping for? He left because he was wise. Because, unmoved by the vagaries of the art market and instead prompted only by the purity and sincerity of that great artistic conversation, he knew he could more deeply undertake his work from the house in Island Bay overlooking the Cook Strait than from a flat in central London. In that task he remained irrepressible, painting, printmaking, mural-making and teaching right up until his death. His artwork stands, powerful and with so much more to be discovered, as one of the best reminders in this country of why the art market is often the worst guide of all to finding the most important and powerful art. For those with eyes of their own, able to look at art without a dealer in their ear or an auction catalogue before them, John Drawbridge has so much to give.

Michael Moore-Jones